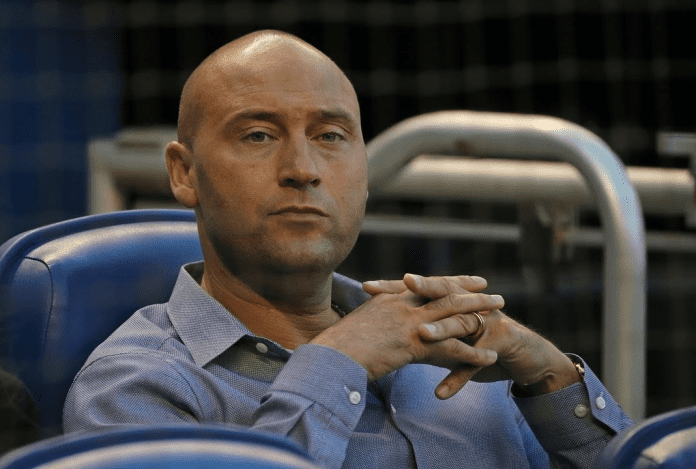

Upon taking over as the Chief Executive Officer of the Miami Marlins, Derek Jeter was immediately dropped into an unfamiliar wilderness with nothing but his wits to get him through. He did not do well. Perhaps he expected to be feted as he was as a player and the media would be intimidated by the prospect of the Jeter “freeze out” for transgressions real and imagined. Or he believed it would be easier than it really is.

His initial management decisions appeared to be based more on hiring people he was familiar with rather than interviewing and finding qualified candidates. He knew Gary Denbo from their time together with the Yankees and Denbo is now the Marlins scouting director. Denbo is no nonsense and polarizing, but he and Jeter are on the same page. Jorge Posada was Jeter’s enforcer in the Yankees clubhouse, waiting for the Michael Corleone-style nod to confront players who offended Jeter’s sensibilities, keeping the captain’s hands clean. He is now a close confidant whose voice is increasingly loud in the Marlins hierarchy.

Jeter also fired showpiece advisors to former owner Jeffrey Loria and future fellow Hall of Famers (once Jeter is elected) Andre Dawson and Tony Perez. Firing them was secondary to the clumsy way it was handled. The hard feelings have yet to subside with Dawson and Perez saying they might boycott Jeter’s Hall of Fame ceremony.

Other dismissals made Jeter appear heartless and inept with haphazardness taking the place of clarity and competence. That said, there’s no handbook to being a sports team owner. Jerry Jones dove into a series of public relations disasters when he purchased the crumbling Dallas Cowboys in 1989.

He awkwardly and some said cruelly fired Tom Landry; made odd comments that, at the time, were laughable; and appeared every bit the unknown businessman from Arkansas he was with little experience in dealing with the media scrutiny that came with such a storied franchise. In retrospect, Landry needed to go; the franchise needed a gutting overhaul; and he had the outsider’s fearlessness and partial cluelessness to do what needed to be done.

It took him three years and he had a Super Bowl champion. Now, that franchise he leveraged himself to the hilt to buy is worth nearly $6 billion.

That’s not to say Jeter will do that same with the Marlins, but immediate reactions are irrelevant. To say it’s wrong for Jeter to try and implement similar teaching protocol as he experienced with the Yankees is presumptuous.

The initial missteps and questions aside, the Marlins appear to be on track to slow and steady improvement.

Retaining Don Mattingly as manager came as a surprise since there was a widespread expectation that Jeter would find someone cheaper. In a way, he did. Mattingly took a significant pay cut to remain as manager. The terms were not reported, but it is believed to have been reduced from the $2.8 million he earned based on the contract he’d signed with Loria to around $2 million.

Still, in an era where new managers are signing contracts for around $600,000 and are essentially puppets, it is a positive that Jeter chose not to cut costs and undermine the manager’s authority either by cutting Mattingly’s salary more than he did or hiring a nameless, faceless automaton.

It’s interesting to note that Jeter is one of the precious few baseball bosses along with Billy Beane and Jerry Dipoto who played in the majors. A key difference is that Jeter is about to be elected to the Hall of Fame while Beane and Dipoto were journeymen. So, for him to shun the trend of hiring a middle-manager to do the front office’s bidding says that he understands the importance of some level of autonomy being granted to the manager and the cachet that develops in the clubhouse and among the players from a manager being in charge.

No amount of change to an organization’s structure will be effective without finding players and the Marlins have done that. Contrary to perception, the prospect-accruing trades of Christian Yelich and Marcell Ozuna and the wise trades of Giancarlo Stanton and J.T. Realmuto have brought depth to the organization.

Lewis Brinson was perceived as the centerpiece of the Yelich trade and is at the make-or-break year in his career. The former first-round pick has been a complete bust so far. The other parts of the trade, infielder Isan Diaz and pitcher Jordan Yamamoto, look like potential cogs to a reasonably bright future. Sandy Alcantara was acquired for Ozuna and was the Marlins’ lone All-Star in 2019; Zac Gallen was acquired in that deal and was spun off to the Arizona Diamondbacks for top-60 MLB prospect, shortstop Jazz Chisholm; Magneuris Sierra is a speedy center fielder. Cuban brothers Victor Victor Mesa and Victor Mesa Jr. are both highly rated prospects.

The Marlins are prioritizing defense and athleticism throughout the organization and that extended to the catcher they acquired in the Realmuto trade, Jorge Alfaro, who has a cannon for an arm and runs surprisingly well for a catcher. The minor-league system, discarded and ignored under Loria, is garnering accolades. With Alcantara, Yamamoto and Caleb Smith, there’s the foundation for a reasonably solid starting rotation. They have pop, speed and defense with their everyday players.

This would be useless without a veteran manager who could keep the players in line and older players who are willing to impart their wisdom on youngsters. Mattingly makes his share of strategic gaffes, but there are few managers as diligent and dedicated as he is. He has expectations and holds the players accountable.

In 2019, there were respected veterans from winning clubs Curtis Granderson and Neil Walker. For 2020, they have signed Corey Dickerson and traded for Jonathan Villar. As the free agent tree shakes itself out, expect one or two Granderson-type signings. (For those expecting Yasiel Puig, it’s certainly possible, but he and Mattingly did not get along in Los Angeles with the Dodgers.)

The Marlins are not contenders in the hellish National League East; they’re not Wild Card contenders in a tough National League; they might never draw the number of fans in Miami necessary to be a viable MLB organization and compete every year; but they are showing positive signs.

As CEO, Jeter should not get the benefit of the doubt, fawning coverage and protection he received as a player. Nor should he be torn to shreds for reasons other than his work as CEO, especially for firing superfluous and overpaid employees like Dawson and Perez. His tenure will be judged for how the team progresses. In that vein, they’re in a much better position now than they were when he took charge.