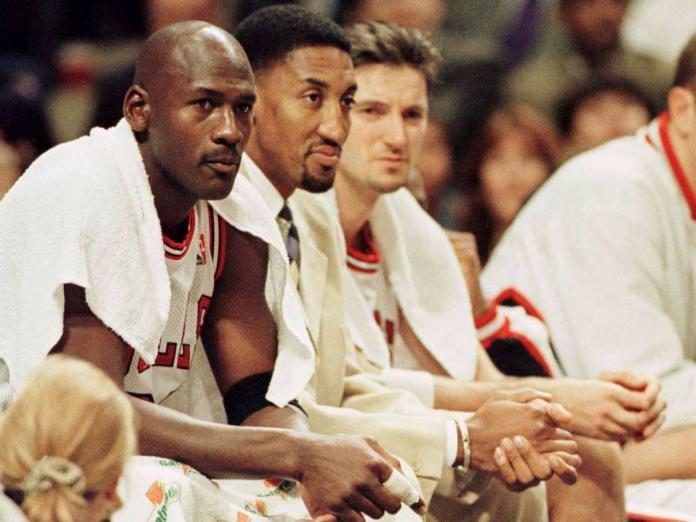

A recurring background theme of The Last Dance was the question as to why the Chicago Bulls dynasty was broken up after it won its third consecutive NBA title and sixth title in eight years. Although the 10-part documentary on ESPN was justifiably referred to as a Michael Jordan career retrospective, there were plenty of backstories from the (mis)adventures of Dennis Rodman to Scottie Pippen’s career ups and downs as Jordan’s Robin, to Steve Kerr, Phil Jackson and Jerry Krause.

Still, the focus was on Jordan and how the Bulls’ rise and fall was inextricably interconnected with him. After the 1998 championship, there was no discussion of keeping the team together for one more run. In retrospect, Jordan laments that decision implying that had owner Jerry Reinsdorf and general manager Krause retreated from their insistence that this time they were really busting it up, he was willing to return on another one-year contract and try for a fourth consecutive title. Already, the Bulls had put on hold the rebuild to go for it again. They were ready to gut it after 1997, but brought the band back together for another world tour.

Looking back, there is endless speculation as to what “would” have happened had the Bulls simply rode it out until it crashed. Shaky theories are discussed such as exclaiming Jordan and the team somehow deserved the right to decide on its own terms when to move on rather than have supervision from the guy who owns the team and the GM who built the dynasty.

Rather than allowing it to run its course organically, there are reasonable explanations for the Bulls’ hierarchy taking the road they did.

What was Michael Jordan’s plan?

How would the Bulls have responded in 1998-99 had they been ready to go for it again and Jordan taken until the summer to decide whether he planned to play before finally saying, “Yeah, know what? I’m exhausted. I’ve accomplished everything I could possibly accomplish. The lockout will make it harder to be mentally and physically prepared. I’m gonna move on to other things”?

What would the Bulls have done then? Jordan certainly had the right to decide on his own whether he was going to play. He never pulled the Brett Favre trick of constantly retiring and un-retiring. It’s entirely possible that he would have informed the club that he was playing in 1998-99 before the lockout ensued. But since the Finals ended on June 14 and the lockout went into effect two weeks later, was he prepared to do that with such a short window to give the front office the necessary time to prepare and convince Jackson to return?

With the lockout, the only personnel decision that the Bulls announced in the aftermath of the 1998 title was Jackson’s resignation. Although Krause told Jackson before the season that he was not returning for 1998-99, Reinsdorf said he offered Jackson the opportunity to return and Jackson said no. Was part of that due to burnout, because he knew the team was on the other side of the mountain, or a combination?

Vince Lombardi quit as Green Bay Packers’ head coach after Super Bowl II with physical and mental exhaustion factors as to why he stepped down. Like Jackson, Lombardi was ready to walk a year earlier. After Super Bowl I – the Packers’ fourth championship during his reign – he returned for one more year and history was rewarded with the Ice Bowl and the subsequent fifth title.

That Packers team, like the Bulls, was old. Bart Starr was 33; Ray Nitschke, 31; Forrest Gregg, 34; Max McGee, 35; Willie Wood, 31. In football player years in the 1960s, that’s ancient. In Lombardi’s final year, observers marveled that he dragged them to another title through a force of will despite their clear decay. The team stayed together under Lombardi’s successor Phil Bengston and rapidly crumbled because the players were finished and the roster was not adequately replenished.

Basketball is slightly different from other team sports because a generational player can take a 20-win team and turn it into a 50-win team as long as he has complementary players surrounding him and a coach who knows how to handle him. LeBron James is proof of that. Jordan, however, was not going to tolerate being the one star on the team without Pippen and Rodman and needing to initiate a new group into his way of doing things for them to know where to be, what to do, how to think and how to win. It might’ve taken two or three years to get them on the same page and he was going year-to-year. At age 35, he had no patience for that, nor should he have.

He says now that he would have been willing to play another year, but what’s he supposed to say when he’s shifting the blame of the breakup of the Beatles away from himself? “It was Krause” is easier because Krause was easy to dislike and mock. There was no true Yoko Ono to hold responsible.

The team was wrung out.

The Bulls were old with every key component in his 30s. Age-related decline can be mitigated only if there’s sufficient motivation to mitigate it. Perhaps Krause and Jackson could have implemented periodic “load management” days in which stars were given rotating breaks long before it became the norm in professional basketball.

In 1997-98, the Bulls might have appeared to be at the top of their game, but there were ominous signs that they were on the way down. The Indiana Pacers carried them to seven games in the Eastern Conference Finals; the Utah Jazz pushed them to six in the NBA Finals. The physical exhaustion is one thing, but as Jordan and others mentioned throughout the documentary, preparing to play and playing was a respite from the outside pressures of being a traveling carnival from town to town as a never ending freak show scrutinized every second of every hour of every day.

An issue that was left undiscussed in The Last Dance was the labor uncertainty. It could have gone either way with that team. The lockout might have benefited the Bulls had they remained together since the 50-game season was a short-term sprint compared to the marathon that the regular season usually was. It gave the players extra time to recover from the daily grind of the prior three seasons in which they played what amounted to two-thirds of an extra season of games in the playoffs.

But would they have wanted to win that fourth title under those circumstances when it would have been rife with “yeah, buts” and the team would likely have been gutted after that anyway?

It was fair for Reinsdorf to question whether it was worth it to pay the likes of Ron Harper, Kerr and others who were approaching age-related decline and who were not good enough by themselves to carry the team, especially when their contracts would be multi-year in exchange for one last year with Jordan/Pippen/Rodman. Paying premium prices just prior to expiration date is an immediate sunk cost. The owner made a management decision to say he could not justify it for the diminishing returns of trying for another championship.

Comparable situations.

In general, ownerships will want to move forward with the dynasty while the financial benefit is there or they will at least break even. In the end, they’re businessmen with a rare few treating their franchise as a point of pride in the community and putting that responsibility over profit.

The New England Patriots maintained because Bill Belichick treats every player like he’s disposable, disposes of them when they’ve fulfilled their usefulness, and he keeps costs reasonable as an addendum to that philosophy. It doesn’t matter who it is, a point proven when Tom Brady departed for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers with no serious attempt on the part of the Patriots to keep him.

Looking at the NFL dynasty that preceded the Patriots – the Dallas Cowboys – and the narrative of their downfall has long been the clashing egos of Jerry Jones and Jimmy Johnson and that they could no longer coexist. That’s partially true. However, the expectations had worn on Johnson as much as Jones elbowing him out of the way on stage did. It was a convenient out that their inability to work together forced the breakup when Johnson wanted to get away from the pressure anyway.

Troy Aikman still laments the Cowboys missing out on their chance to be the Patriots, but Johnson – a good friend of Belichick – is not so tunneled in his interests as Belichick is. Belichick doesn’t let outside stressors bother him. Johnson did.

Winning three straight titles on two different occasions as the Bulls did is borderline miraculous. The allure of the Bulls is that they went out on top of the world; still dominant; still glossy; forever beautiful and untarnished by age and infirmity. Did they want to sully that by waiting until they lost to say, “Ok. That’s it”? Did they want to copy the previous NBA dynasties of the Los Angeles Lakers, Boston Celtics and, to a lesser extent, the Detroit Pistons by running it into the ground?

Keeping the group together until it reaches its natural conclusion removes the ambiguity of “what might have been.” Sometimes, though, “what might have been” is preferable to “what was.” With the Bulls, it could not have gotten better. It could only have gotten worse. Based on that, Reinsdorf was right to move on. Their greatness is in suspended animation with no passing of the torch nor sad final scene. Competitively, they might have wanted it to end on the court. Aesthetically, it’s better it ended the way it did.

Stay up to date with the latest news trends and original content by following us on Twitter and liking us on Facebook.